- Biology of Perennials

- Growing Perennials in Georgia

- Soil pH and Mineral Nutrients

- Fertilization

- Fall is the Best Time to Plant

- Bed Preparation

- Perennial Bed Design

- Selection and Planting

- Plant Selection Tips

- Beware of Invasives!

- General Culture

- Perennial Bed Renovation

- Marketing Perennials in the Landscape and Managing Customer Expectations

- Perennial Planting Gallery

- Table 1. Quick reference of recommended perennial genera* for sun.

- Table 2. Quick reference of recommended perennial genera* for shade.

- Table 3. Perennials generally avoided by deer.

- Table 4. Selected perennials for Georgia.

- Additional Resources

Whether in a commercial installation or residential garden, perennial plants can be successfully used to offer more landscaping choices, distinguish your firm from the competition and create a niche for your landscape business. Perennial plants are complex, and it is best to contract or hire a professional landscape architect for the design phase and train knowledgeable staff in proper maintenance later on.

With a rich history of plant introductions, hybridization and selection, we can now enjoy plants in Georgia that until recently were once found only on a remote mountain slope in Asia or a tropical rainforest in South America. The perennial plant trade offers more than 3,600 species and cultivated varieties, and more are added each year. With such an extensive palette, how do you choose the right plant? Our advice is to follow three simple rules:

- stick to species and selections that are known to do well in the area; the “bread-and-butter” plants;

- match the optimum growing requirements; plant the “right plant in the right place”; and

- spend the extra time to maintain each species at its peak performance (e.g., additional nutrition, mid-summer trimming, regular deadheading); go the extra mile.

You don't have to plant 50 species in one landscape, or always use the latest and most fashionable cultivars - you could make a stunning display with five species or varieties that have been in the trade for 20 years. That said, you should strive to familiarize yourself with new hybrids that have improved tolerance to shade/sun, fewer pest problems, require less water and pruning, and have an extended flowering time. This information can be acquired from books, annual trade conferences and Extension publications (refer to “Additional Resources” at the end of this publication). An excellent way to see how new selections perform is to visit the University of Georgia Trial Gardens located on campus in Athens (http://ugatrial.hort.uga.edu/).

This publication is intended to provide the basics of perennial plant biology, ideas on design and installation, and information on cultivation and maintenance of perennial beds. It should also serve as a quick guide for the most common and recommended perennials for Georgia. Common-sense tips from a professional landscaper's perspective are also included.

Biology of Perennials

The term “perennial” in the broadest sense means plants that live for more than two years. This broad definition includes shrubs and trees that retain woody stems above ground in winter, including ferns, cacti, succulents, grasses, bulbs, some herbs and groundcovers. For the home gardener, however, it means a plant with stems that usually die back in winter and a root system from which new foliage and flowers grow the following year. Most perennials have herbaceous stems (e.g., Coreopsis, Achillea, Echinacea, Liatris), but a few develop woody stems (e.g., hardy hibiscus, rosemary). There is also a category of plants, called “tender perennials,” which are annuals that may over-winter occasionally, depending on how severe the winter is (Figure 1). A true perennial has a capacity to survive from one year to the next.

Figure 1. Colocasia (elephant ear; front left, heart-shaped foliage), a tender perennial, is shown here emerging from the ground along with Hosta, a perennial (back of bed, gray foliage). Tender perennials have become very popular in the trade; however, you should be familiar with each species and cultivar, as their cold tolerance varies.

Figure 1. Colocasia (elephant ear; front left, heart-shaped foliage), a tender perennial, is shown here emerging from the ground along with Hosta, a perennial (back of bed, gray foliage). Tender perennials have become very popular in the trade; however, you should be familiar with each species and cultivar, as their cold tolerance varies.Growing Perennials in Georgia

While perennial plants are found in almost every natural habitat around the world, not all plants can grow well when they are cultivated in a different region of the globe. The best plant performance is achieved when the landscape habitat closely matches the plant's endemic environment. Until recently, most plant catalogs listed only the cold hardiness zone when describing how far north a plant can be expected to survive (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Georgia Plant Hardiness Zone Map. Zones are based on average minimum winter temperatures. Many other factors, such as summer heat, summer night temperatures, humidity and rainfall, affect plant performance and adaptability.

Figure 2. Georgia Plant Hardiness Zone Map. Zones are based on average minimum winter temperatures. Many other factors, such as summer heat, summer night temperatures, humidity and rainfall, affect plant performance and adaptability.Georgia has a diverse range of cold hardiness zones, ranging from zone 6a in the northeast corner of the state to zone 9a in the southern coastal part of the state.

Plants growing in Georgia also face a challenging combination of high summer temperatures and high humidity (Figure 3). Academicians, nurserymen, growers, and landscape professionals have found that growing perennial plants in the Southeast justifies using a heat tolerance map as well -- one that describes a plant's adaptability to summer heat. The American Horticultural Society (www.ahs.org) provides information on plant heat tolerance in a detailed interactive map.

Figure 3. Average days above 900 F (30-year annual averages rounded to next highest class) in the state of Georgia.

Figure 3. Average days above 900 F (30-year annual averages rounded to next highest class) in the state of Georgia.Heat tolerance is more difficult to evaluate than cold tolerance; plants respond to cold by dying, to heat by slowly declining. High night temperatures increase respiration; for every 160F rise in temperature, respiration rate doubles. Plants use up their stored reserves, leading to reduced vigor, small foliage and weak, stunted plants and. The effects of heat damage are subtler than those of extreme cold, which can kill a plant quickly. Heat damage can first appear in many different parts of the plant -- flower buds may wither, leaves may droop or become susceptible to pests, chlorophyll may disappear so that leaves appear white or brown, or roots may cease growing. Plant death from heat is slow and lingering.

Georgia also has a very diverse ecology, with more than 100 distinct environments and at least eight major habitats. These are generally grouped within three geological regions: Mountains / Northwest, Piedmont and Coastal Plain. Figure 3 shows that the Coastal Plains experience more days of temperatures over 900 F compared to more northern regions (Mountains), which plays a major role in plant performance across the state.

The last two factors to consider when planting perennials are rainfall and soil. The entire state, including the Mountains, receives moderate to heavy rain, which varies from 45 inches in central Georgia to approximately 75 inches around the northeastern part of the state. The Coastal Plains experience hot, humid summers with frequent afternoon thunderstorms and mild, drier winters. Wet, cool springs are typical.

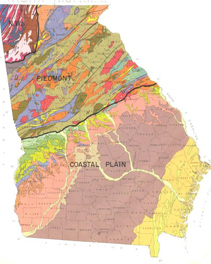

Figure 4. Georgia soil map (for detailed information, visit www.dot.ga.gov). Colors indicate different soil types.

Figure 4. Georgia soil map (for detailed information, visit www.dot.ga.gov). Colors indicate different soil types.Rainfall, when considered with various soils, affects perennial plant survival and adaptability to Georgia's climate. The soils in Georgia are varied; generally, the Coastal Plains have sandy, well-drained soils that are poor in organic matter, while the Piedmont and Mountain regions have heavier clay or clay-loam soils that retain water well, with organic matter present in some areas (Figure 4).

Drainage becomes a very important factor in plant survival. Inadequate drainage in clay soils creates favorable conditions for root rots, and insufficient moisture retention in sandy soils causes plant stress from drought. In fact, more perennials die from wet winter soils than from cold in Georgia. Amend perennial beds with organic matter to improve soil conditions.

Research has shown that plant growth in Georgia climates is typified by earlier-flowering, taller plants with weaker stems due to accumulated heat - more so than in more northern climates. Tall forms tend to collapse without support; therefore, dwarf selections are usually more effective. Fertilizer may not need to be applied as generously, particularly for tall plants as additional growth is not desired. Leggy, lanky growth and fewer flowers result if too much nitrogen is applied.

Soil pH and Mineral Nutrients

Since perennials are expected to live in a certain area for many years, it is very important to be sure the soil is amended to fit the plant's needs. In addition to organic matter, pay attention to soil pH. Too high or too low soil pH may affect nutrient uptake, stress the plant and reduce the plant's chances of surviving more than one year.

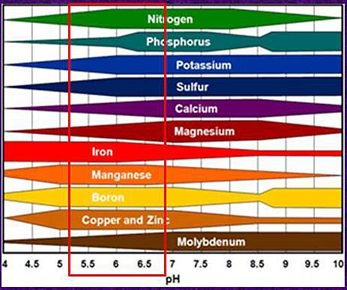

Figure 5. Nutrient availability chart. The red box shows the pH range in which mineral nutrient uptake is optimal.

Figure 5. Nutrient availability chart. The red box shows the pH range in which mineral nutrient uptake is optimal.Most perennials prefer a pH between 5.2 and 6.7 (slightly acidic). Soil pH affects nutrient uptake (Figure 5). This “Goldilocks” range assures that two important micronutrients -- iron (Fe) and manganese (Mn) -- are being absorbed by the plant roots in optimal concentrations. If the pH is below 5, both of these elements can interfere with the uptake of other nutrients. If the pH is higher than 7, Fe and Mn can become deficient. Symptoms of nutrient deficiency include yellow (chlorotic) leaf tips and young foliage (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Symptoms of phosphorus deficiency.

Figure 6. Symptoms of phosphorus deficiency. Figure 6. Symptoms of nitrogen deficiency.

Figure 6. Symptoms of nitrogen deficiency. Figure 6. Symptoms of magnesium deficiency.

Figure 6. Symptoms of magnesium deficiency.

Figure 6. Symptoms of iron deficiency.

Figure 6. Symptoms of iron deficiency.

Two other common deficiencies are phosphorus (P) and magnesium (Mg). Phosphorus deficiency typically occurs in winter and manifests as purple or bronze foliage color (on plants with evergreen foliage). Do not direct-supplement with phosphorus; instead, apply a balanced fertilizer, such as 10-10-10, in the spring as leaves emerge and soil warms up. Magnesium deficiency symptoms include interveinal chlorosis of lower leaves (Figure 6). Georgia soils are lower in this important macronutrient; use magnesium sulfate (Epsom salts) to remedy this deficiency. Nitrogen (N) deficiency is typified by chlorosis of older leaves (mild), progressing to overall chlorosis (moderate to severe).

Periods of excessive rain or drought can affect nutrient levels and uptake. In winter, some perennials that have evergreen foliage can become purple or bronze in color. This may be a normal condition in the winter, but a warning sign of deficiencies in late spring. Calcium and magnesium may be depleted. Only a soil test and a foliage test will determine the right ratio of nutrients to add to correct the problem.

Fertilization

A soil test, available through your county Extension office, is the best way to determine which fertilizer analysis is most suitable. As a general guideline, most ornamental plants will benefit from a fertilizer having its primary nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium [N-P-K]) in a 3-1-2 or 4-1-2 ratio. A 12-4-8 fertilizer, for instance, is a 3-1-2 ratio, and a 16-4-8 fertilizer is a 4-1-2 ratio. Research shows that phosphorus, the middle number in the analysis, is held by soils and does not leach with rains or irrigation as much as nitrogen or potassium do, so it is usually needed in lower amounts.

The most common types of fertilizer applied to perennial beds in the spring are general-purpose 10-10-10 (N-P-K), 8-8-8 or 16-4-8. Other analyses, however, are sometimes more suitable for a given species (Table 4). The recommendations are based on pounds of nitrogen per 1,000 square feet per season.

- Heavy: 3 applications: 1 pound of 10-10-10/100 sq. ft./season: one at transplant, one three to four weeks later, and another one three to four weeks after that.

- Moderate: 2 applications: 1 pound 10-10-10/100 sq. ft./season: one at transplant and one mid-season.

- Low: 1 application: 1 pound 10-10-10/100 sq. ft. at transplant or in early spring before growth resumes.

Fertility products can be formulated to deliver the plant food over a short- or long-term period. Be sure to use a formula that fits your needs. Spring growth may require fast- acting fertilizer products, whereas summer fertilization may require a slow-release product, including organic fertilizer. Remember that shade areas and sandy soils require different levels of fertility than sunny garden soils.

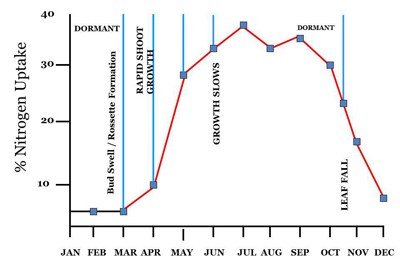

Figure 7. Nitrogen uptake throughout the year shows that fertilizer should be applied in spring during shoot growth.

Figure 7. Nitrogen uptake throughout the year shows that fertilizer should be applied in spring during shoot growth.Below is a simple calculation for how much fertilizer to apply per bed.

- For dry fertilizers (e.g., 16-4-8), divide the percentage of N into 10 (10/16 = 0.6 pounds). The resulting number is the pounds of N to be applied per 100 sq. ft.

- Determine the square footage of the bed (e.g., 5' x 50', or 250 sq. ft.).

- Multiply 250 sq. ft. x 0.6 (the application rate per 100 sq. ft.) then divide into 100 = 1.5 pounds.

- The resulting number (1.5 pounds) is how much 16-4-8 fertilizer to apply to a 5' x 50' perennial bed.

For further information on different fertilizer formulations and application rates, refer to “Care of Ornamental Plants in the Landscape,” ½ûÂþÌìÌà Extension Bulletin 1065, and “How to Convert an Inorganic Fertilizer Recommendation to an Organic One,” ½ûÂþÌìÌà Extension Circular 853.

Perennials are much like shrubs in that they may require high levels of fertility early in spring or summer, when they put on growth, and low fertility the remainder of the year (Figure 7). The ability of a plant to take up nitrogen is also a function of season. Once leaves are lost to frost, perennials do not need fertilizer.

Fall is the Best Time to Plant

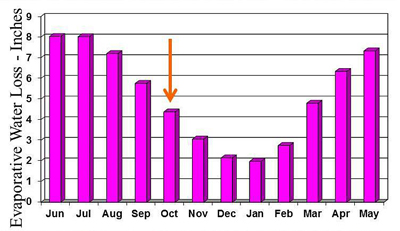

Figure 8. Monthly evaporation rates (20-year average) for Athens, Ga. Plant perennials in October when evaporative water loss is reduced (arrow).

Figure 8. Monthly evaporation rates (20-year average) for Athens, Ga. Plant perennials in October when evaporative water loss is reduced (arrow).There are many reasons for planting in the fall. The most important reason is to give the new plants a chance to develop a sizable root system in the absence of high temperatures and transpiration rates (loss of water from foliage). Root development may take several months, and by having this occur in the winter months, the plant is not stressed. A well-developed root system will be better able to withstand dry periods and times of high water loss due to high evaporation in summer. Evaporation rates, and hence water demand, drops off in October (Figure 8).

Figure 9. Raised beds not only improve drainage but also provide better plant display. Organic compost should be thoroughly tilled.

Figure 9. Raised beds not only improve drainage but also provide better plant display. Organic compost should be thoroughly tilled.Bed Preparation

Perennials require careful bed preparation to establish successfully. Remove all plant debris, amend the soil, till to 12 to 18 inches and add fertilizer to new perennial beds. Using a coarse-grade compost or organic supplement will help the bed retain moisture longer (Figure 9). Coarse granite sand also is a good amendment for perennial beds if drainage needs to be improved.

Perennial Bed Design

Planting schemes for perennial beds are usually mixed plantings incorporating annuals, perennials, shrubs and trees (Figures 10-11).

Shrubs and trees provide the “backbone” of the landscape as well as winter interest, while annuals are used as year-round complementary color (e.g., pansies and other winter annuals, and petunias and other summer annuals). The annuals are either placed to the outside of the bed or interspersed among the perennials and woodies; the latter is utilized in the first year or two of the installation to provide color and interest while the other plants are still establishing.

Figure 10. Perennials are skillfully interspersed among shrubs and trees in this commercial landscape in Atlanta. Daylily 'Happy Returns' (behind bench), Russian sage (lavender blooms) and shasta daisy (white blooms) are surrounded by boxwood hedge.

Figure 10. Perennials are skillfully interspersed among shrubs and trees in this commercial landscape in Atlanta. Daylily 'Happy Returns' (behind bench), Russian sage (lavender blooms) and shasta daisy (white blooms) are surrounded by boxwood hedge.

Figure 11. Perennials (Euphorbia, Canna, Buddleia) are used as a backdrop to frame a water feature, while annuals (vinca, coleus) provide color and textural interest (early summer).

Figure 11. Perennials (Euphorbia, Canna, Buddleia) are used as a backdrop to frame a water feature, while annuals (vinca, coleus) provide color and textural interest (early summer). Figure 11. Perennials (Euphorbia, Canna, Buddleia) are used as a backdrop to frame a water feature, while annuals (vinca, coleus) provide color and textural interest (late summer).

Figure 11. Perennials (Euphorbia, Canna, Buddleia) are used as a backdrop to frame a water feature, while annuals (vinca, coleus) provide color and textural interest (late summer).

In general, there are three types of perennial beds (Figure 12):

- Island bed: A freestanding garden, usually kidney- shaped and often raised to promote drainage, can be viewed from all sides;

- Perennial border: Double or single border with a backdrop of a wall, fence or woody shrubs that is generally viewed from one side;

- Naturalized area: Established in an area of native plants (e.g., woodland garden or natural stream).

Figure 12. Perennial border

Figure 12. Perennial border Figure 12. Island bed

Figure 12. Island bed Figure 12. Naturalized area

Figure 12. Naturalized area

When designing large perennials beds that are to be viewed from a distance or by passing vehicles, a simple theme, both in color and species, is most suitable (Figure 13).

Figure 13. A complementary three-color theme, Vitex (blue), Echinacea (pink) and Rudbeckia (yellow), provides drama and grabs the viewer's attention.

Figure 13. A complementary three-color theme, Vitex (blue), Echinacea (pink) and Rudbeckia (yellow), provides drama and grabs the viewer's attention. Figure 13. Panicum 'Heavy Metal' provides a backdrop for Rudbeckia fulgida.

Figure 13. Panicum 'Heavy Metal' provides a backdrop for Rudbeckia fulgida.

Figure 13. On a smaller scale, the same blue- red-yellow theme works well with blue and red salvias and yellow tarragon.

Figure 13. On a smaller scale, the same blue- red-yellow theme works well with blue and red salvias and yellow tarragon.

On the other hand, when designing smaller beds and inviting a closer look, a more intense theme with many colors and textures is appropriate (Figure 14).

Figure 14. This mixed annual and perennial bed may appear too “busy” but the goal was to have customers spend more time in the adjoining retail area.

Figure 14. This mixed annual and perennial bed may appear too “busy” but the goal was to have customers spend more time in the adjoining retail area.Yellow, orange and red are the most dramatic colors and should be used sparingly. Green, blue and purple recede and should be grouped together. When creating a vibrant color border, surround the bold colors with white or silver to avoid a harsh, gaudy look. Common two-color complementary schemes are yellow and purple, red and green, and orange and blue. Use plants with small flowers en masse (e.g., Russian sage) and plants with large blooms (e.g., hardy hibiscus) as specimens.

Selection and Planting

Planning is the key to success when designing and installing a perennial bed. Know the plant's requirements for sun or shade, moisture and nutrition (Tables 1, 2, 4). One of the most common pitfalls is placing species that require full sun for best growth and bloom in areas that get fewer than six hours of sunshine (Figure 15).

Figure 15. Right plant in the right place. Stachys, lamb's ear and Coreopsis (red “x”) are full-sun plants struggling under the heavy shade in this bed. Hosta (green star) is a proper choice, while purple heart (Tradescantia, purple star) can tolerate shade but for intense foliage color needs more sun. Plantings are of the same age and cultivar located throughout one commercial account.

Figure 15. Right plant in the right place. Stachys, lamb's ear and Coreopsis (red “x”) are full-sun plants struggling under the heavy shade in this bed. Hosta (green star) is a proper choice, while purple heart (Tradescantia, purple star) can tolerate shade but for intense foliage color needs more sun. Plantings are of the same age and cultivar located throughout one commercial account. Figure 15. Crocosma exhibits fewer blooms in partial shade (above) compared to no shade (below).

Figure 15. Crocosma exhibits fewer blooms in partial shade (above) compared to no shade (below). Figure 15. Crocosma exhibits fewer blooms in partial shade (above) compared to no shade (below).

Figure 15. Crocosma exhibits fewer blooms in partial shade (above) compared to no shade (below).Plant Selection Tips

- Know the habit and final size of the perennial to prevent a vigorous plant overtaking less vigorous specimens (Table 4). Spacing perennials is critical as many start small and grow large in width and height. Space plants according to their mature size or the size they will achieve in the third year of growth. Pay close attention to species and cultivars; for example, blue sage (Salvia guaranitica) can grow to 5 feet tall and wide, while lady red salvia (Salvia coccinea 'Lady-in-Red', a perennial in most of the state) will not grow larger than 2 feet. Some perennials (e.g., Salvia leucantha) do not perform well if young plants receive competition from other plants for light, water and nutrients during the establishment phase. When planted too far apart, on the other hand, more mulch will be needed to control weeds and keep the soil cool and moist. Unless a sufficient layer of mulch is maintained, soil evaporation may cause heat stress and delay growth. Additional space may be required for perennials that form a colony (e.g., Liatris). Bottom line: use a planting density that allows sufficient room for plants to grow successfully to maturity.

- Know the soil type preference and the pH requirements to ensure the likelihood of survival year after year.

- Know pest and disease tendencies, which will help you plan for problems that may arise in the future so that you can build a preventive pest control program. For instance, species in the daisy family (Asteraceae) are prone to powdery mildew, while aphids can devastate a milkweed (Figure 16).

Figure 16. Aphids on Asclepias, milkweed.

- Know the life span to help you plan replacements and establish where the plant will be placed in the landscape. Most long-lived plants should be placed towards the back and side of the bed, or in the middle, to allow replacement of less long-lived specimens without disturbing the more permanent specimens.

- Group plants by growth rates to facilitate the division process (see “Bed Renovation”).

- Place perennials in triangle formations to maximize flowering and foliage effects.

- Plant groups of each species/cultivar rather than spotting single plants throughout the bed.

- Leave grass foliage and heads for winter interest.

- Know the bloom period to plan a continuous bloom sequence and year-round interest. Arrange plants so certain areas of the bed are in bloom at same time.

- Choose masses of fewer selections to increase visual impact and simplify maintenance. This will also help less experienced maintenance staff to discern weeds from the perennials, especially in spring when plants are emerging.

- Add annuals/shrubs (see Figure 11) and bulbs for color/texture (Figure 17).

Figure 17. Daffodils are interplanted with Rudbeckia in this island. After the daffodil blooms fade, their foliage needs to remain to feed the underground bulb. During this time the Rudbeckias screen the daffodil foliage.

Figure 17. Daffodils are interplanted with Rudbeckia in this island. After the daffodil blooms fade, their foliage needs to remain to feed the underground bulb. During this time the Rudbeckias screen the daffodil foliage.Beware of Invasives!

There are quite a few perennials that are so vigorous that they can become invasive. Lythrum salicaria, Solidago species and Physostegia virginiana can be invasive in cultivated gardens, as can Monarda and Oenothera. Many of these species are native to nearby states, but not native to Georgia. Plants from other countries may also escape cultivation and become truly invasive and damaging to local environments (Figure 18). Be sure the plants you select are not invasive. Check www. gaeppc.org and www.eddmaps.org/species/ for information on invasive species in Georgia and surrounding states and alternatives for non-native invasive plants.

Figure 18. Even though irises are commonly used in rainwater gardens, Iris pseudacorus (yellowflag), I. syberica (Syberian iris), I. pallida (sweet iris) and I. ensata (Russian iris) are considered invasive species by the Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health at the University of Georgia (www.eddmaps.org). The yellow-flowered species in this planting is Iris pseudacorus.

Figure 18. Even though irises are commonly used in rainwater gardens, Iris pseudacorus (yellowflag), I. syberica (Syberian iris), I. pallida (sweet iris) and I. ensata (Russian iris) are considered invasive species by the Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health at the University of Georgia (www.eddmaps.org). The yellow-flowered species in this planting is Iris pseudacorus.A good way to handle more aggressive species is to place them in a challenging location in the planting. For example, perennial plumbago (Ceratostigma plumbaginoides), an excellent perennial for sun, can be planted on a slope or in a rock garden with limited soil in order to check its growth. Be on the lookout for new hybrids and cultivars that are sterile (i.e., not-reseeding) or less vigorous (dwarf), as they offer the good qualities with none of the bad.

Many ornamentals have variegated foliage, including stripes or white/yellow stripes on foliage margins, or overall cream, yellow, chartreuse or gold leaves. As a general rule of thumb, these varieties are not as vigorous as the all-green form. This can be both a positive, because the plant will not be as aggressive, and a negative, because the plant may not thrive and adapt well due to reduced photosynthesis and limited reserves. Always install the right plant in the right place and be ready to properly maintain it (Figure 19).

Popularity of native plants is growing. Be willing to explore their potential. Not only will you be protecting Georgia natural ecosystems, but you will also provide long-term benefits, such as food and shelter for many native insects and animals, which can control invasive pests, reduce the need for pesticides and offer a sustainable way to maintain healthy landscapes. For more information, refer to Native Plants for Georgia under “Resources.”

Figure 19. Lysimachia 'Aurea' is often planted as an evergreen groundcover in the shade; however, there are several issues: L. nummularia is species listed as invasive; under optimal moist and shady conditions, it quickly spreads, and the slower-growing yellow-leafed form 'Aurea' often reverts back to the green form (shown here), which will take over. To check its growth, do not plant under optimal conditions and trim away any green shoots as they appear.

Figure 19. Lysimachia 'Aurea' is often planted as an evergreen groundcover in the shade; however, there are several issues: L. nummularia is species listed as invasive; under optimal moist and shady conditions, it quickly spreads, and the slower-growing yellow-leafed form 'Aurea' often reverts back to the green form (shown here), which will take over. To check its growth, do not plant under optimal conditions and trim away any green shoots as they appear.General Culture

Pot Sizes

There are four popular sizes used in the perennial plant trade: 3-1/2” pot, 4-1/2” Perennial, #1 Perennial and #2 Perennial (for detailed information on pot sizes and volumes, refer to http://www.anla.org/%5Cdocs%- 5CAbout%20ANLA%5CIndustry%20Resources%- 5CANL AStandard2004.pdf) . Each has its advantages and disadvantages. The smaller sizes are suitable for low-budget installations, but will dry out faster and need more frequent irrigation until they get established. In addition, they may not be in bloom until later. The larger sizes have instant impact because of plant size and bloom, and their establishment period is shorter; on the downside, they can be cost-prohibitive.

Mulch

Mulches provide many benefits, including holding moisture in the soil, helping prevent weed growth, inhibiting certain soil-borne foliar diseases and insulating plant roots from temperature extremes during summer and winter. The best mulch is organic, fine-textured and non-matting. Examples include pine straw, pine bark mini-nuggets, hardwood chips and cypress shavings. Fall leaves make an excellent and economical mulch and add valuable humus back to the soil (thus improving soil structure as they decompose). Along with yard trimmings, leaves are suitable for residential accounts. Pecan hulls, a by-product of the pecan industry, are used successfully as mulch in south Georgia. Grass clippings are not a good source of mulch because they tend to mat down and inhibit the flow of water and nutrients into the soil. They also may introduce weeds. Inorganic mulches, such as rock, gravel and marble, are good soil insulators but they absorb and re-radiate heat in the landscape, increasing water loss from plants.

How much mulch to apply depends upon irrigation plans, local soils and local weather. If you are designing a low-water-use bed, 4 to 6 inches of pine straw or pine bark will be required. An average residential garden will require a 3- to 5-inch layer. On commercial installations with irrigation, 2 to 3 inches of mulch will do.

Weed Control

Because perennials live their lives in one place, seasonal weeds can be a problem. Weeds compete with perennials for water, nutrients and sunlight. Weeds can be controlled mechanically (by hand, with mulch and landscape fabric) or chemically (with herbicides). For chemical control, pre-emergence and post-emergence herbicides are available. Pre- emergence herbicides control weeds in the early stages of weed seed germination, and post-emergence herbicides are used to kill established weeds. Be aware that pre-emergence herbicides need water to move (activate) into the zone where weed seeds germinate, while post-emergence herbicides need a certain period of dryness after application. Also bear in mind that a single application of pre- or post-emergence herbicide will not provide 100 percent weed control; for that you will need to combine several weed control techniques.

Use pre-emergence herbicides in medians and other limited-access beds. Mulch bark impregnated with pre-emergence herbicide has recently become available on the market. For specific information on weed control, consult ½ûÂþÌìÌà Georgia Bulletin 979, Weed Control in Home Lawns, available at your county extension office or at caes.uga.edu/publications.

Wildlife

Urbanization destroys wildlife habitat, pushing adaptable wildlife species to move into urban/suburban landscapes. Landscapes contain many plant species that provide food and shelter for wildlife. As a landscaper you have a choice: inhibiting incursions by unwanted animals or promoting wildlife visits (e.g., hummingbirds, bees and butterflies). Increased contact with wildlife may either lead to customer complaints or delight.

Animals that do the most damage to ornamental plants in the landscape include deer and rabbits. Table 3 lists perennial plants generally avoided by deer. More information on mechanical or chemical means of keeping wildlife from perennial plantings can be found under “Resources.”

Planning Maintenance

For best performance, perennial beds need to be maintained, which demands an investment of labor and time. Make sure that you include this extra time and labor when you prepare a bid or estimate. Make a good case to the customer about why this expense is in their best interest. Use knowledgeable staff to maintain residential accounts with numerous species (train your staff to recognize what is a weed and what is an ornamental!)

Figure 20. Salvia nemorosa (Woodland sage) blooms in early summer.

Figure 20. Salvia nemorosa (Woodland sage) blooms in early summer. Figure 20. By midsummer only the seedheads are visible. If the plants were deadheaded after the first flush, a second flush of blooms could have appeared, providing a nice backdrop to the Lantana.

Figure 20. By midsummer only the seedheads are visible. If the plants were deadheaded after the first flush, a second flush of blooms could have appeared, providing a nice backdrop to the Lantana.Removing spent flower heads, called deadheading, is very important to most perennials (Figure 20). For example, Verbascum species will die mid-summer if the spent flowers are not removed. This is because too many food reserves (i.e., sugars, the product of photosynthesis) go into the seeds, and our hot Georgia summers use up a great deal of reserves with respiration. The plant literally starves to death. Removing the flower head before it goes to seed saves photosynthates for growth. Plants such as Echinacea (purple cone flower) will simply stop growing and stop putting up new flowers if they are not deadheaded. For continuous bloom and less disease, remove spent flowers regularly. In addition, perennials with tendencies to reseed will be discouraged from doing so.

Perennial Bed Renovation

In Georgia, it is recommended that perennial beds be dug up and renovated every three years. Renovation reduces soil compaction, adds back organic matter, increases plant spacing and improves air circulation, thereby reducing disease and invigorating the planting (Figure 21). As with initial planting, removing the plants, dead leaves and mulch before adding compost and amendments is recommended. Replanting is usually done the same day or the very next day. In essence, the perennial underground and aboveground mass is divided and smaller sections are planted back in the bed.

The general rule of thumb is to divide spring-flowering perennials in the fall and fall-flowering perennials in the spring.

Figure 21. When perennials grow in one place for extended time, there is competition for water and nutrients. Roots/rhizomes also become overcrowded, which was the case in this Iris colony (above), leading to loss of vigor and death in the center of the clump (as happened with this Pampas grass (below)).

Figure 21. When perennials grow in one place for extended time, there is competition for water and nutrients. Roots/rhizomes also become overcrowded, which was the case in this Iris colony (above), leading to loss of vigor and death in the center of the clump (as happened with this Pampas grass (below)).

Figure 22. Dividing perennials with fibrous roots (arrow indicates growing point).

Figure 22. Dividing perennials with fibrous roots (arrow indicates growing point).Fibrous roots (Figure 22). Many perennials form colonies of plants that have interconnecting fibrous root systems (e.g., Phlox, Salvia, Helianthus and Eupatorium). The only reliable method of division is to identify groups of growing points, lift large sections of the root mass with a pitchfork or shovel and then pull the clumps apart to obtain individual sections with growing points.

Figure 23. Dividing perennials with rhizomes involves cutting the underground stem into sections.

Figure 23. Dividing perennials with rhizomes involves cutting the underground stem into sections.Rhizomatous Perennials (Figure 23). Many perennials, such as Iris, Canna, daylily and blue anise sage, have rhizomes that must be lifted, washed and then hand cut. Each section of root must have a new eye or growth area.

Dividing Hostas (Figure 24). Hostas are particularly easy to divide, as the individual plants form separately. Simply lift the entire colony, remove soil from the roots by applying a spray of water, then pull the clumps apart.

Figure 24. Division of Hosta.

Figure 24. Division of Hosta.Spreading Perennials (Figure 25). Spreading perennials can often be divided as large clumps. Each clump is planted as a unit. Some perennials, such as thrift and Dianthus, can also be propagated by making individual stem cuttings. Remove clusters from the outer areas of the colony to reduce its size. Pull the sections apart into individual stem pieces. A rooting hormone may expedite root formation when applied to the base of the stems, but many perennials do not need a rooting hormone if cuttings are taken in early spring or mid-fall. Place individual sections in prepared soil, and bury the lower one-third of the stem. Water-in cuttings thoroughly and keep them moist for the next few weeks. If this procedure is followed in the fall, each stem will root and form a new plant by spring. These new plants can be re-dug mid-summer and transplanted.

Figure 25. Dividing spreading perennials involves cutting the creeping stems into sections and replanting them.

Figure 25. Dividing spreading perennials involves cutting the creeping stems into sections and replanting them.Marketing Perennials in the Landscape and Managing Customer Expectations

Using perennials in landscape installations can be a rewarding experience for your customers and a profitable one for you; however, there are some common misconceptions regarding perennials that you and your customer need to be aware of.

Perennials are not low-maintenance -- they require watering, fertilizing, shaping, deadheading, fall mulching, spring cleaning, dividing, replacing and insect, disease and weed control. Some perennials grow best when divided every few years. Perennial bed renovation should be considered every three to five years. All of these tasks can be built into the maintenance bid and properly addressed from the outset.

Perennials take time to fill space. A popular proverb describes their growth: “The first year they sleep, the second year they creep, and the third year they leap!” Many plants start small and get very large. Make sure you leave them adequate “elbow room” and assure your customer that they are properly spaced.

Customers want flowers and butterflies but they may not recognize that the same sweet nectar brings other insects as well (Figure 26). Bees and wasps may be a nuisance and some people are allergic to their sting. You need to let your customer know that next to the mailbox may not be the best location for that “butterfly magnet.”

Figure 26. Along with the beautiful Tiger Swallowtail butterfly and the Silver Spotted Skipper, at least 5 bumblebees (circled in red) are enjoying the blooms of this Agastache.

Figure 26. Along with the beautiful Tiger Swallowtail butterfly and the Silver Spotted Skipper, at least 5 bumblebees (circled in red) are enjoying the blooms of this Agastache.Perennial plants can be a valuable addition to your plant palette; they can bring you return customers and boost sales if you follow three simple rules: plant the right plant in the right place, use plants that do well in the area, and spend a few extra resources on maintenance.

Perennial Planting Gallery

The following photos are of commercial installations using perennial plants.

Russian sage and shasta daisy surrounded by boxwood hedge, which provides support for the tall-stemmed perennials.

Russian sage and shasta daisy surrounded by boxwood hedge, which provides support for the tall-stemmed perennials. A dry, full-sun, raised planter with thyme (center and insert, in bloom), evergreen sedum (chartreuse) and hensand- chicks (burgundy).

A dry, full-sun, raised planter with thyme (center and insert, in bloom), evergreen sedum (chartreuse) and hensand- chicks (burgundy). Mixed bed with variegated Liriope, Canna and Liatris.

Mixed bed with variegated Liriope, Canna and Liatris. Lysimachia 'Aurea' with dwarf Loropetalum (burgundy foliage) provide good colors, contrast and evergreen groundcover; the small size of the perennials works well with the crape myrtles to provide good visibility for traffic.

Lysimachia 'Aurea' with dwarf Loropetalum (burgundy foliage) provide good colors, contrast and evergreen groundcover; the small size of the perennials works well with the crape myrtles to provide good visibility for traffic. All-perennial bed with Iris, Gaura, lamb's ear and yarrow.

All-perennial bed with Iris, Gaura, lamb's ear and yarrow. Canna interplanted with Brazilian verbena. The aggressive Canna is constrained by the narrow concrete bed, while the tall flower stems of the Verbena offer visual interest and contrast to the coarse Canna foliage.

Canna interplanted with Brazilian verbena. The aggressive Canna is constrained by the narrow concrete bed, while the tall flower stems of the Verbena offer visual interest and contrast to the coarse Canna foliage. Ice plant (pink flowers), Sedum 'Autumn Joy' and bird nest Picea. The drought-tolerant evergreen perennials are a good choice for a South-facing bed, and the short habit allows for clearance from the windows; also notice the wavy pattern formed by the ice plant.

Ice plant (pink flowers), Sedum 'Autumn Joy' and bird nest Picea. The drought-tolerant evergreen perennials are a good choice for a South-facing bed, and the short habit allows for clearance from the windows; also notice the wavy pattern formed by the ice plant. Heuchera interplanted with Lycoris (red flower); both work well in the narrow bed and against the white siding.

Heuchera interplanted with Lycoris (red flower); both work well in the narrow bed and against the white siding. Sedum edged with Liriope for a client who wanted evergreen and low-maintenance.

Sedum edged with Liriope for a client who wanted evergreen and low-maintenance. Yarrow, shasta daisy and Miscanthus 'Gold Bar' work well in this drought-tolerant, low-maintenance bed.

Yarrow, shasta daisy and Miscanthus 'Gold Bar' work well in this drought-tolerant, low-maintenance bed. A mixed-shade bed with two varieties of Heucheras -- lenten rose and cast iron plant -- combines a good use of evergreen foliage and foliar textures.

A mixed-shade bed with two varieties of Heucheras -- lenten rose and cast iron plant -- combines a good use of evergreen foliage and foliar textures. A single-species planting of Hosta 'Patriot' under evergreen Japanese cedar.

A single-species planting of Hosta 'Patriot' under evergreen Japanese cedar.Table 1. Quick reference of recommended perennial genera* for sun.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Common Name | Scientific Name |

| Yarrow | Achillea | Helen’s Flower | Helenium |

| Anise Hyssop | Agastache | Orange Sunflower | Heliopsis |

| Hollyhock | Alcea | Daylily | Hemerocallis |

| Lady’s Mantle | Alchemilla | Rose Mallow | Hibiscus |

| Ornamental Onion | Allium | Candytuft | Iberis |

| Arkansas Blue Star | Amsonia | Iris | Iris |

| Bluestem Grass | Andropogon | Lantana | Lantana |

| Windflower | Anemone | Lavender | Lavandula |

| Wormwood | Artemisia | Rose Campion | Lychnis |

| Butterfly Weed | Asclepias | Shasta Daisy | Chrysanthemum |

| Aster | Aster | Gayfeather | Liatris |

| False Indigo | Baptisia | Bee Balm | Monarda |

| Bellflower | Campanula | Catmint | Nepeta |

| Bachelors Buttons | Centaurea | Switch Grass | Ravenna |

| Perennial Plumbago | Ceratostigma | Poppies | Papaver |

| Tickseed | Coreopsis | Balloon Flower | Platycodon |

| Larkspur | Consolida | Phlox | Phlox |

| Crocosmia | Crocosma | Black Eyed Susan | Rudbeckia |

| Pinks | Dianthus | Russian Sage | Perovskia |

| Coneflower | Echinacea | Sage | Salvia |

| Joe Pye Weed | Eupatorium | Lavender-Cotton | Santolina |

| Spurge | Euphorbia | Pincushion Flower | Scabiosa |

| Ice Plant | Delosperma | Stonecrop | Sedum |

| Blanket Flower | Gaillardia | Lamb’s Ear | Stachys |

| Whirling Butterflies | Gaura | Stoke’s Aster | Stokesia |

| Cranesbill | Geranium | Speedwell | Veronica |

| * Not all species in each genus are suitable for Georgia — for species and cultivars, refer to Table 4. | |||

Table 2. Quick reference of recommended perennial genera* for shade.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Common Name | Scientific Name |

| Bugbane | Actaea | Leopard Plant | Ferfugium |

| Lady’s Mantle | Achemilla | Lenten Rose | Helleborus |

| Anemone | Anemone | Coral Bells | Heuchera |

| Columbine | Aquilegia | Plantain Lily | Hosta |

| Jack-in-the-Pulpit | Arisaema | Ligularia | Ligularia |

| Goatsbeard | Aruncus | Virginia Bluebells | Mertensia |

| Wild Ginger | Asarum | Cinnamon Fern | Osmunda |

| False Spirea | Astilbe | Mayapple | Podophyllum |

| Painted Fern | Athyrium | Jacob’s Ladder | Polemonium |

| Pig Squeak | Bergenia | Solomon’s Seal | Polygonatum |

| Bugloss | Brunnera | Christmas Fern | Polystichum |

| Turtlehead | Chelone | Lungwort | Pulmonaria |

| Lily-of-the-Valley | Convallaria | Meadow Rue | Thalictrum |

| Bleeding Heart | Dicentra | Foam Flower | Tiarella |

| Autumn Fern | Dryopteris | Toad Lily | Tricyrtus |

| Snakeroot | Eupatorium | Trillium | Trillium |

| * Not all species in each genus are suitable for Georgia — for species and cultivars, refer to Table 4. | |||

Table 3. Perennials generally avoided by deer.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Common Name | Scientific Name |

| Yarrow | Achillea | Iris | Iris |

| African Lily | Agapanthus | Lavender | Lavandula |

| Anise Hyssop | Agastache | Cardinal Flower | Lobelia |

| Ornamental Onion | Allium | Shasta Daisy | Chrysanthemum |

| Elephant Ears | Alocasia/Colocasia | Gayfeather | Liatris |

| Bluestem Grass | Andropogon | Bee Balm | Monarda |

| Windflower | Anemone | Catmint | Nepeta |

| Columbine | Aquilegia | Oregano | Oreganum |

| Jack-in-the-Pulpit | Arisaema | Poppies | Papaver |

| Wormwood | Artemisia | Russian Sage | Perovskia |

| Butterfly Weed | Asclepias | Mayapple | Podophyllum |

| Aster | Aster | Christmas Fern | Polystichum |

| False Indigo | Baptisia | Green Jerusalem Sage | Phlomis |

| Boltonia | Boltonia | Switch Grass | Ravenna |

| Bellflower | Campanula | Rosemary | Rosmarinus |

| Bachelors Buttons | Centaurea | Black Eyed Susan | Rudbeckia |

| Perennial Plumbago | Ceratostigma | Sage | Salvia |

| Tickseed | Coreopsis | Lavender-Cotton | Santolina |

| Pinks | Dianthus | Pincushion Flower | Scabiosa |

| Foxglove | Digitalis | Stonecrop | Sedum |

| Coneflower | Echinacea | Hens-and-Chicks | Sempervivum |

| Joe Pye Weed | Eupatorium | Lamb’s Ear | Stachys |

| Spurge | Euphorbia | Stoke’s Aster | Stokesia |

| Ice Plant | Delosperma | Tansy | Tanacetum |

| Blanket Flower | Gaillardia | Foamflower | Tiarella |

| Sweet Woodruff | Gallium | Meadow Rue | Thalictrum |

| Perennial Sunflower | Helianthus | Society Garlic | Tulbaghia |

| Lenten Rose | Helleborus | Speedwell | Veronica |

Additional Resources

½ûÂþÌìÌà Extension publications

“How to Convert an Inorganic Fertilizer Recommendation to an Organic One,” Circular 853.

“Native Plants for Georgia: Part II. Ferns,” Bulletin 987-2.

“Native Plants for Georgia: Part III. Wildflowers,” Bulletin 987-3

“Native Plants for Georgia: Part IV. Grasses and Sedges,” Bulletin 987-4

“Using Milorganite to Repel White-Tailed Deer from Perennials,” Circular 889-1

“Deer-Tolerant Ornamental Plants,” Circular 985

“Repellents and Wildlife Damage Control,” Circular 1021

“Care of Ornamental Plants in the Landscape,” Bulletin 1065

Other Extension publications

“Total Plant Management of Herbaceous Perennials,” Bulletin 359. University of Maryland Extension.

Books

Herbaceous Perennial Plants: A Treatise on their Identification, Culture, and Garden Attributes. 3rd Ed. A. Armitage. 2008. Stipes Publishing, IL.

Status and Revision History

Published on Dec 23, 2013

Published with Full Review on Sep 01, 2016

Published with Full Review on May 27, 2020

Published with Full Review on May 19, 2022