A classic example of a North American species that undergoes a great migration is the monarch butterfly, Danaus plexippus Linnaeus (Figure 1). Monarchs travel on air currents and cross more than 3000 miles in winter to reach their overwintering sites.

Figure 1. Adult monarch butterfly and larva.

Photos: (adult) Steven Katovich, Bugwood.org; (larva) Jonathan Armstrong, University of Southern California, Bugwood.org.

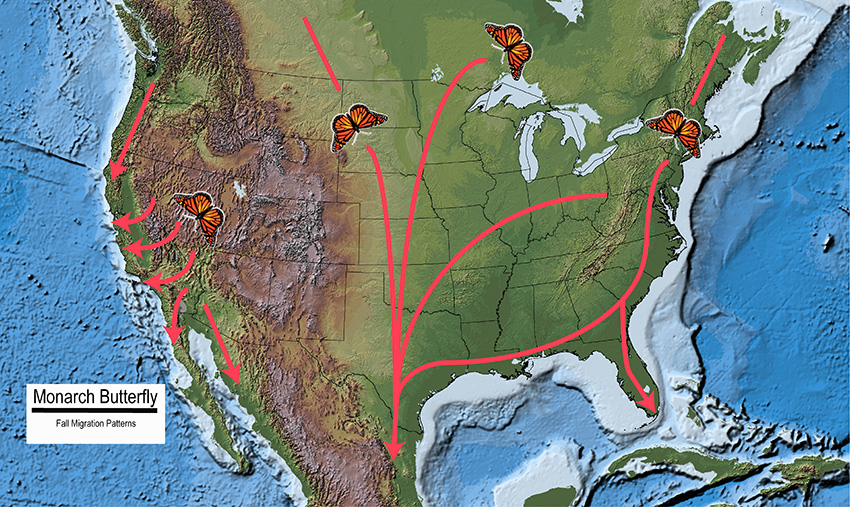

Broadly, there are two populations of monarch butterflies based on their migration patterns—eastern and western. The eastern population breeds in the east and overwinters in central Mexico (Figure 2). The western population breeds primarily west of the Rocky Mountains and overwinters in coastal California. Recent studies suggest that these two populations are interbreeding, and the Rocky Mountains are not necessarily a barrier separating these two populations.

Figure 2. Autumn migration of both eastern and western monarch butterfly populations in North America.

Image: U.S. Geological Survey National Atlas.

The overwintering sites of monarchs were not revealed to the world until the 1970s (Figure 3). They overwinter on fir trees in the oyamel fir forest highlands of central Mexico (Figures 4 and 5). The western population migrates across the western states, returning to overwinter in coastal California forest groves (Figure 6).

Figure 3. Cover of National Geographic magazine with a story about the first discovery of a monarch butterfly overwintering site in Mexico.

Photo: Harry O. Yates III, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org.

Figure 4. The overwintering sites of the eastern populations of monarch butterflies are on trees in the mountains of Michoacan, Mexico.

Photo: Harry O. Yates III, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org.

Figure 5. Overwintering monarch butterflies on fir trees in the mountains of Michoacan.

Photo: Harry O. Yates III, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org.

Figure 6. Overwintering western populations of monarch butterflies on a eucalyptus tree.

Photo: William M. Ciesla, Forest Health Management International, Bugwood.org.

Why is the Monarch Butterfly Important?

Unlike bees, which are excellent pollinators of many plants, the monarch butterfly is not an excellent pollinator. It is not good prey for other insects or birds, either. The monarch butterfly emerged as a symbol of nature conservation or environmental health and is now a conservation icon. The monarch is regarded as the favorite native insect of North America and is the state butterfly in seven U.S. states.

Life Cycle and Migration

As depicted in Figure 7, the adult butterfly lays eggs on milkweed (Asclepias spp.), and the eggs hatch in 3 to 5 days at 72–82 °F (22–28 °C). The larvae consume milkweed foliage and develop through five larval stages in approximately 11 to 18 days in the summer. The fifth instar forms a chrysalis (pupa) on the plant or any other structure they can find, such as a building or fence. The adult monarch butterfly emerges from the pupa in 8 to 14 days in the summer.

Figure 7. The full lifecycle of a monarch butterfly, egg to adult, takes 22 to 37 days. The adult lays eggs that hatch in 3–5 days; the larval stages last 11–18 days; the pupa stage lasts 8–14 days, and then adults emerge from the pupal casing.

Photos: (eggs) John A. Davidson, University of Maryland–College Park, Bugwood.org; (adult) Charles T. Bryson, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Bugwood.org; (first instar) courtesy of Dickinson County (Iowa) Conservation Board; (late larvae and pupae) Edward L. Manigault, Clemson University donated collection, Bugwood.org. Note. This lifecycle is adapted from “Monarch Butterfly Biology,” by the U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture (https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/pollinators/Monarch_Butterfly/biology/index.shtml).

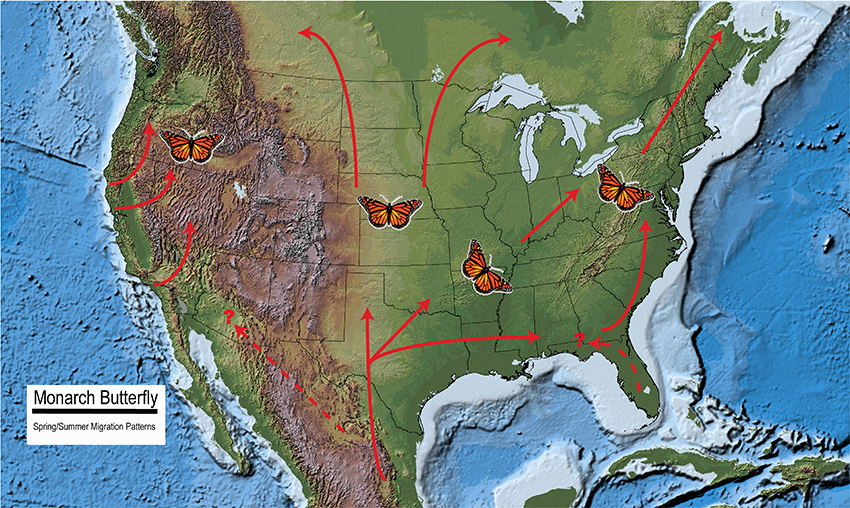

The eastern population of monarch butterflies overwinters from October to March in central Mexico. The overwintering adults fly north by the end of April. They become reproductively mature, breed, lay eggs in the southern U.S., and go through the first generation in May (Figure 8). The second and third generations move further north. The larvae of the fourth generation develop in the North during August, but their adults migrate to Mexico for overwintering. This means adults of one generation fly south to overwintering sites, whereas adults of up to three generations fly north.

Figure 8. Spring migration of eastern and western monarch butterfly populations in North America.

Image: U.S. Geological Survey National Atlas.

The eastern population migration flights are along “monarch highways,” referred to as “flyways” (indicated by the red lines in Figure 2). Depending on where they originate in northern America, there could be many flyways, and these flyways unite to form a single “super flyway” in central Texas. The generation of monarchs returning to overwintering sites in central Mexico is flying there for the first time. They fly during the daytime and roost on pine, fir, and cedar trees during the nighttime.

Larval Hosts

The larval stages of monarchs are host-plant specialists. The larvae feed and develop on milkweed and other species closely related to Asclepias spp. This means they must feed on milkweed to develop and will not survive on other host plants. Milkweed contains a network of pressurized latex canals, and the latex oozes out when cut. It contains cardenolides, which are toxic to insects. The latex also is a glue that sets quickly once exposed to air. When insects feed on milkweed, the latex often intoxicates the insect, or they get stuck to the glue. Younger monarch caterpillars cut out a trench, nipping the veins before feeding on the leaf tissue within the trench. The late-instar larvae cut the veins either at the midvein or the petiole and let the latex ooze out before feeding. They sequester the toxic chemicals in their bodies and are brightly orange-colored to warn predators that they carry poison.

Adult Hosts

Adult monarch butterflies forage on any flowers they can find along their paths north or south. They need nectar as a sugar source and other nutrients to sustain flight. When they start flying north in the spring, they need to feed on nectar to reach Texas. Similarly, in mid- to late summer, on their journey south, they need to consume nectar from flowers to reach Mexico. What they feed on during their journey southward helps them sustain their return flight and overwinter in Mexico. Adult monarchs do not feed at all during the winter. Along the migration journey (both northward and southward), adults feed from patches of flowering plants, which appear as islands or stopping-off points to refuel their energy needs. Thus, it is critical to plant a variety of flower gardens with good nectar resources, especially in urban areas.

Population Decline

Monarch butterfly populations are showing a declining trend. As the overwintering habitat in Mexico is destroyed by logging or deforestation activities, they have fewer and fewer places to overwinter. The migratory monarch is now on the red list of endangered species created by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, an authority on global biodiversity. Other factors contributing to their decline such as diseases, pesticide use, and loss of larval hosts (i.e., milkweed) are on the rise. The larvae need milkweed to develop, and the adults need nectar for migration and survival day-to-day, so more nectar sources and milkweed plants are needed to sustain their migration patterns. More flowering plants and milkweeds can help conserve the migrating monarchs, especially when planted along farm-reserved lands and urban gardens.

A few popular programs can help landowners build these habitats, such as the Monarch Waystation program (https://www.monarchwatch.org/waystations/) or the Million Pollinator Garden Challenge (/), among others.

Considerations When Building a Monarch Garden:

- Structured gardens with mulch will harbor more monarch caterpillars than nonstructured, open gardens. Plan your plantings so there is vegetation at various levels and heights throughout the garden.

- Gardens with unimpeded north–south access recruit more monarchs than gardens with impeded access. If planted close to a structure (e.g., a home, barn, or shed), ensure the garden has north–south access by planting along the side of the structure facing east or west.

- More monarch caterpillars are found on taller milkweed species (Figure 9), like swamp milkweed (A. incarnata), showy milkweed (A. speciosa), and common milkweed (A. syriaca), than on butterfly milkweed (A. tuberosa). Tall milkweeds attract two to three times more eggs and larvae than do shorter Asclepias species.

- Tall milkweeds also attract larger bees, such as bumblebees and honeybees. For attracting smaller native bees, butterfly milkweed (A. tuberosa) and whorled milkweed (A. verticillata) are the best (Figure 9).

- Plant milkweeds on the perimeter of the garden (along the mulch) for more eggs and larvae. If the milkweeds are hidden among other plant species, it is difficult for the adults to find the milkweed. Accessibility to plants is critical to harboring more eggs and larvae.

- Swamp, butterfly, and green milkweeds are less likely to spread from where they are originally planted, whereas common, showy, and narrowleaf milkweeds spread easily with aggressive rhizomes. These rapidly spreading plants are better for large areas, such as golf course roughs, conservation areas, etc.

- Many nativars (cultivars of native milkweed) are available in the market, and they are as good as wild or straight milkweed species in recruiting monarch larvae.

- Avoid creating a garden that is an ecological trap where the recruited monarchs die because of other factors, such as when a garden is planted near high road traffic. Avoid creating opportunities for invaders, such as invasive European paper wasps (Figure 10) and tropical milkweed (A. curassavica; Figure 9E; see below for additional information).

- Butterfly boxes create ideal conditions for European paper wasps to thrive. Remove them!

- Rearing monarchs in captive conditions for conservation is not recommended and it reduces or dilutes the genetic diversity, fitness, and migratory success of the species.

Figure 9. (A) Swamp milkweed, Asclepias incarnata; (B) common milkweed, A. syriaca; (C) butterfly milkweed, A. tuberos; (D) eastern whorled milkweed, A. verticillate; (E) tropical milkweed, A. curassavica L.; (F) narrow leaf milkweed, A. fascicularis Dcne.

All photos from Bugwood.org: (A) Rob Routledge, Sault College; (B) Ohio State Weed Lab, The Ohio State University; C) John D. Byrd, Mississippi State University; (D) Vern Wilkins, Indiana University; (E) Rebekah D. Wallace, University of Georgia; (F) Joseph M. DiTomaso, University of California–Davis.

European Paper Wasps (Polistes dominula Christ)

Native to Mediterranean countries, European paper wasps (Figure 10) are invasive wasp species in North America. These wasps are widespread throughout the continental U.S.—from California in the west to Maine and Kentucky in the east. It is an urban pest that is adapted to thrive in all sorts of human dwelling structures, such as on a home, garage, or shed, under the deck, etc. These wasps feed on caterpillars, including monarch larvae (young and late stages), which they chop up to feed young wasp larvae. Young caterpillars are particularly vulnerable to being attacked and killed; late-stage caterpillars drop to the ground when attacked.

Figure 10. European paper wasp, Polistes dominula Christ.

Photo: David Cappaert, Bugwood.org.

Tropical Milkweed

Tropical milkweed (Figure 9E) is a perennial and will not die during winter. The monarch butterflies perceive the lack of senescence (or dying off) as a signal to continue laying eggs and will not leave the host. This phenomenon affects the migration of monarch butterflies, and they stay on the host for an extended period. Dieback of the host in winter signals to the monarchs to return to overwintering sites in Mexico. As they spend more time on tropical milkweed, monarchs become more susceptible to diseases, such as one caused by the pathogen Ophryocystis elektroscirrha. The butterflies emerging from infected pupae are often deformed and cannot properly fly. At high temperatures, tropical milkweed can have toxic levels of cardenolides and actually kill the developing monarch larvae.

References

Baker, A. M., Potter, D. A. (2018, June 6). Colonization and usage of eight milkweed (Asclepias) species by monarch butterflies and bees in urban garden settings. Journal of Insect Conservation, 22, 405–418.

Baker, A. M., Potter, D. A. (2018, August 14). Japanese beetles’ feeding on milkweed flowers may compromise efforts to restore monarch butterfly habitat. Scientific Reports, 8, 12139.

Baker, A. M., Potter, D. A. (2019). Configuration and location of small urban gardens affect colonization by monarch butterflies. Frontiers Ecol. Evol., 7, 474.

Baker, A. M., Potter, D. A. (2020). Invasive paper wasp turns urban pollinator gardens into ecological traps for monarch butterfly larvae. Scientific Reports, 10, 9553.

Satterfield, D., Maerz, J. C., Hunter, M. D., Flockhart, D. T. T., Hobson, K., Norris, D. R., Streit, H., de Roode, J. C., & Altizer, S. (2018). Migratory monarchs that encounter resident monarchs show life-history changes and higher rates of parasite infection. Ecology Letters, 21(11), 1670–1680.

Thogmartin, W. E., Widerholt, R., Oberhauser, K., Drum, R. G., Diffendorfer, J. E., Altizer, S., Taylor, O. R., Pleasants, J., Semmens, D., Semmens, B., Erickson, R., Libby, K., & Lopez-Hoffman, L. (2017). Monarch butterfly population decline in North America: Identifying the threatening processes. Royal Society Open Science, 4(9), 170760.

U.S. Forest Service. (n.d.) Monarch butterfly. U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Xerces Society. (n.d.) Monarch butterfly conservation.

Status and Revision History

In Review on Feb 07, 2024

Published on Feb 29, 2024