Dennis W. Hancock, Extension Forage Agronomist, Department of Crop and Soil Sciences

Ray Hicks, County Extension Coordinator, Screven County

Jeremy M. Kichler, County Extension Coordinator, Macon County

Robert C. Smith III, County Extension Coordinator, Morgan County

Introduction

The ecological term “grasslands” aptly describes most forage systems in Georgia. This is appropriate because the grasses dominate most pastures and hayfields. This is not by happenstance. Grasses have a tremendous ability to regrow following defoliation because they have a growing point that remains low (often below the soil surface) and an ability to put up new tillers (shoots).

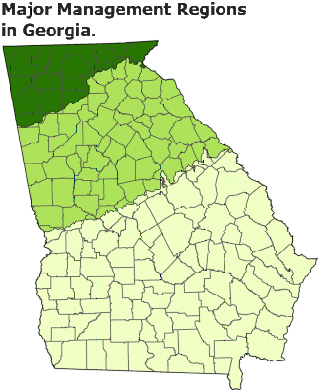

The geographic and environmental diversity of Georgia allows for the extensive use of both cool and warm season grass species (Figure 1). In general, cool season grass species provide higher nutritional quality than warm season grasses. In contrast, warm season grasses generally yield more than cool season grasses. Each type and species, however, offers its own unique qualities and benefits to the forage system. In this section, the most important grass species in Georgia are introduced and discussed.

Figure 1. Pastures and hayfields are generally grass-based. Georgia's geographic and environmental diversity contributes to a wide range of grasses used for pasture and hay production.

Figure 1. Pastures and hayfields are generally grass-based. Georgia's geographic and environmental diversity contributes to a wide range of grasses used for pasture and hay production.

I) Limestone Valley/Mountains Region

Pasture:

- Tall Fescue*

- Cool season annuals **

- Warm season annuals**

Hay:

- Tall Fescue*

- Seeded Bermudagrasses*

- Hybrid Bermudagrasses**

- Warm season annuals**

II) Piedmont Region

Pasture:

- Tall Fescue*

- Common Bermudagrass*

- Cool season annuals*

- Warm season annuals**

Hay:

- Hybrid Bermudagrass*

- Tall Fescue**

- Warm season annuals**

III) Coastal Plain Region

Pasture:

- Common Bermudagrass*

- Hybrid Bermudagrasses*

- Bahiagrass*

- Cool season annuals*

- Warm season annuals*

Hay:

- Hybrid Bermudagrass*

- Warm season annuals**

*Very common practice.

**Not a typical practice, but possible.

Cool Season Annual Grasses

Cool season annual grasses are productive in late fall and spring and are widely grown throughout Georgia. They provide high quality grazing either overseeded in permanent pastures or on a prepared seedbed.

New varieties of cool season annual grasses are released periodically, so it is important to examine the yield comparison trials in ½ûÂþÌìÌÃ’s . The data are published annually in the “Small Grains Performance Tests.” These reports are available on the Variety Testing program’s website or through your county Extension office.

Annual Ryegrass

Annual Ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum)

Annual Ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum)

Annual ryegrass (commonly referred to as simply “ryegrass” in Georgia) is a well-adapted winter annual that can be planted in prepared seedbeds or overseeded onto perennial grass sods for late winter and spring grazing. Some newer varieties may even provide some late fall grazing if planted early and/or into a prepared seedbed. Ryegrass is also often seeded in mixtures with a small grain and/or clover. It is a prolific seed producer and will reseed in pastures (if allowed to go to seed). Ryegrass has a later grazing season than the small grains and can be grazed until early May in south Georgia and late May or early June in north Georgia when moisture is adequate.

Ryegrass is one of the highest quality forages that can be grown in Georgia, often providing more than 70 percent TDN and 18 percent CP if grazed in the late vegetative stage. High quality (56 to 64 percent TDN and 10 to 16 percent CP) can also be expected in the early stages of seedhead development. However, quality and palatability of late season forage can be low due to disease (mainly rust) and maturity.

Since it can produce at such high quality when properly managed, it often is planted for high quality hay or silage cuttings (usually one or two) in the spring. It is also commonly planted into dormant bermudagrass hayfields. This is a recommended practice, but the ryegrass should be mowed, cut for hay, or grazed before the bermudagrass comes out of dormancy. Ryegrass harvesting should be timed (usually late March in south Georgia and late April in north Georgia) to prevent it from suppressing the spring emergence of bermudagrass.

Hay harvests in late April or May are often difficult because of rainfall. Care should be taken to ensure that ryegrass is dried to a moisture level that is appropriate for safe storage of hay (15 percent moisture for round bales; 18 percent moisture for square bales). Alternatively, ryegrass haylage and baled silage can be used to conserve this high quality forage when rainfall is of concern.

Rye

Rye (Secale cereale)

Rye (Secale cereale)

Rye is the most drought-tolerant and winter-hardy small grain grown in Georgia. It is also more tolerant of soil acidity than other winter annual grasses. It can be planted in early fall and usually produces good grazing by late fall. Rye produces more forage in late winter than the other small grains. Since it matures earlier than any other winter annual, it is well-suited for early grazing or haylage production on crop land that must be prepared in early spring for summer row crops. Forage quality declines rapidly in spring as the plants become stemmy and leaf production decreases. Varieties differ in maturity and some will begin seedhead production as early as mid-January in south Georgia. Mixing rye varieties will enable more even production of high-quality forage. However, blending rye with ryegrass or annual legumes will extend the grazing period.

Oat

Oat (Avena sativa)

Oat (Avena sativa)

Oat is a small grain often used for winter forage production in Georgia. When seeded in mid-fall, it furnishes forage in late fall and spring. Oat is not as cold hardy as rye and can winter-kill during harsh winters. This crop produces more forage in spring than rye and can be cut for hay or silage; however, it is not as productive as ryegrass in the spring and is not very grazing tolerant. Planting oat in a mixture with ryegrass and/or a winter annual legume will produce more total forage over a longer grazing season than oat alone.

Wheat

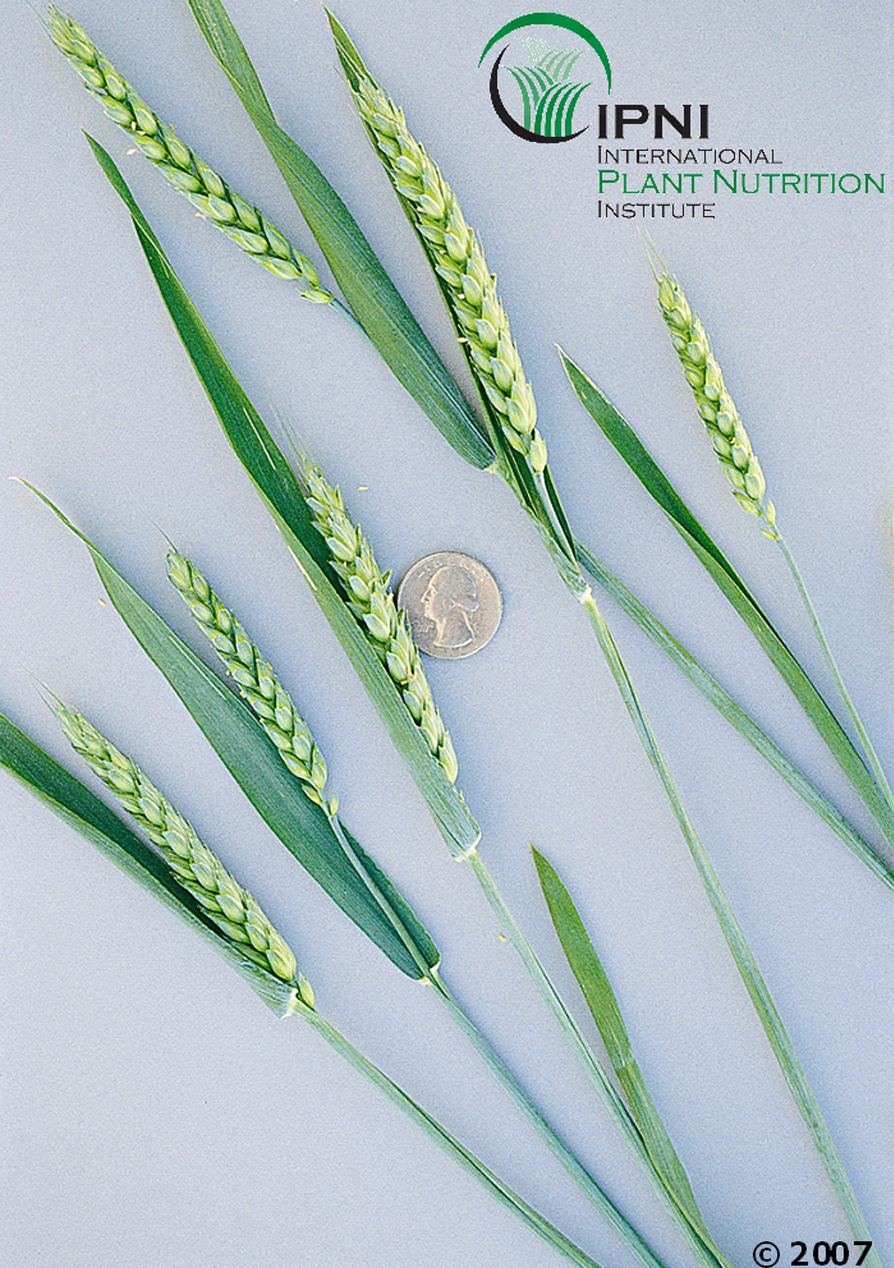

Wheat (Triticum aestivum)

Wheat (Triticum aestivum)

Wheat is a winter-hardy small grain that provides forage in late fall (some varieties), early winter, and spring and is well-suited to grazing or silage. When ensiling wheat, cut the crop in the late boot to early bloom stage of growth. For best results, wilt the crop to 65 to 75 percent moisture (25 to 35 percent dry matter) before chopping and ensiling.

Wheat that has been planted for grain production can be grazed in late fall and winter without substantial losses in grain production; however, it is critical that animals are not allowed to graze (cut) the growing point. Animals should be removed before the wheat starts to joint (usually early March in south Georgia and mid- to late March in north Georgia). Wheat works well in mixtures with other small grains, ryegrass, and clovers.

Triticale

Triticale (pronounced trit-ih-KAY-lee) is a hybrid of wheat and rye that has been evaluated for grain and forage production. It grows tall like rye, but matures later like wheat. It has a relatively wide leaf and can produce high-quality forage if it is grazed or cut in vegetative or early reproductive stages.

Unfortunately, triticale yields have historically been less than wheat. It matures fast like rye, and its forage quality declines rapidly after seedhead development. Until recently, triticale has been bred for grain production. However, newer varieties have better forage production and, when harvested correctly, can provide excellent quality. Some of these newer varieties work well as single-cut silage or haylage crops, particularly for use in dairy rations. Triticale does not perform well under grazing in Georgia.

Barley

Barley is a small grain that is occasionally used on fertile sites in north Georgia but is not widely grown in south Georgia. It is winter-hardy but produces less forage and is more susceptible to disease than the other small grains. Thus, barley is not a recommended forage species in Georgia.

Establishment of Cool Season Annual Grasses

Establish winter annuals on well-drained, fertile soils when possible. If the sites are somewhat poorly-drained, ryegrass will be a better choice than the small grains. Treat small grain seed with an approved fungicide prior to planting. Seedling diseases such as Phytophthora, Rhizoctonia, Pythium, and others reduce stands when planted in the warmer months of September and October, especially in south Georgia.

These crops can be seeded between late August and early October in the Limestone Valley/Mountains region, early September and mid- to late October in the Piedmont region, and late September to late October in the Coastal Plain region. If late fall and early winter grazing is desired (lower Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions only), plant at the earlier dates of these ranges and into a prepared seedbed. Do not overgraze these pastures during the late fall or early winter. For best results, maintain at least 2 1/2 inches of stubble height.

If practical, prepare seedbeds two to three weeks before planting. This will allow the soil to settle and firm, thus improving seed germination and seedling development. Although deep soil preparation is not necessary for the grazing crop, deep tillage may benefit row crops planted in the spring.

Seed can be placed more precisely with a drill or cultipacker seeder than by broadcasting and disking. When seed are broadcast, increase the seeding rate by 25 to 30 percent to allow for variable seed placement. Plant small grain seed one to 1 1/2 inches deep in moist soil. Do not plant ryegrass seed deeper than 1/2 inch. When planting mixtures of ryegrass and small grains, it may be easier to control the seeding depth by broadcasting ryegrass seed and then drilling the small grain seed into the seedbed. Seeding rates for winter annual crops are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Seeding rates for annual cool season grass species.

| Species |

Seeding Rate* |

| Grown Alone |

Mixture |

| ———— lbs/acre ———— |

| Ryegrass |

25 - 30 |

15 - 25 |

| Rye |

90 - 120 |

60 - 90 |

| Wheat |

90 - 120 |

60 - 90 |

| Oats |

90 - 120 |

60 - 90 |

| Triticale |

90 - 120 |

60 - 90 |

| *Use higher seeding rates when seed is broadcast and lower seeding rates when planting into a prepared seedbed or no-tilled into existing sod (overseeding pasture). |

Apply 40 to 50 lbs. of nitrogen (N) per acre at planting or soon after the plants emerge to increase growth, tillering (thickening of the stand), and provide earlier grazing. A second application of 40 to 50 lbs. of N per acre should be applied in mid-winter to increase winter and spring forage production. Because ryegrass is longer-lived, a third application of 40 to 50 lbs. of N per acre may be needed in early spring when ryegrass is used for late spring grazing, hay, or as a silage crop. Rates of N in excess of these amounts may result in substantial N losses to leaching and excessive growth during the winter. Fresh, tender growth that occurs when N is in excess could be damaged by extremely cold weather.

Grazing Cool Season Annual Grasses

Grazing is one of the best uses for cool season annual grasses; however, the species differ somewhat in their tolerance of grazing. Ryegrass and rye are generally very tolerant of repeated grazing, while triticale generally does not regrow quickly. Barley, wheat, and oats have poor grazing tolerance.

Grazing can begin as soon as the plants are well-established and have accumulated four inches (or more) of growth. Begin with a light stocking rate and gradually increase as the growing conditions improve and forage growth rate increases. Consider the forage quality, nutritional needs of the animals, amount of forage present, availability, and the cost of other feed items when deciding how many animals to graze. Restricting the animal’s time on the paddock, rotating animals between paddocks, or using strip grazing techniques will improve utilization and reduce damage to the stand. Grazing when the soil is too wet (when animals’ hooves can bog in the soil) can severely damage winter annuals and will decrease potential production.

Consider the need for conserved forage, crop rotations that may follow, and the value of available forage when deciding when to terminate grazing. If ryegrass and legumes are permitted to produce mature seed, a volunteer crop will often develop the following fall.

Cool Season Perennial Grasses

Tall Fescue

Tall Fescue is a cool season perennial that is well-adapted to areas north of the Fall Line/Sand Hills area. Over one million acres of tall fescue are used for pasture in north Georgia. Under irrigation and managed grazing, tall fescue is also productive in the Coastal Plain.

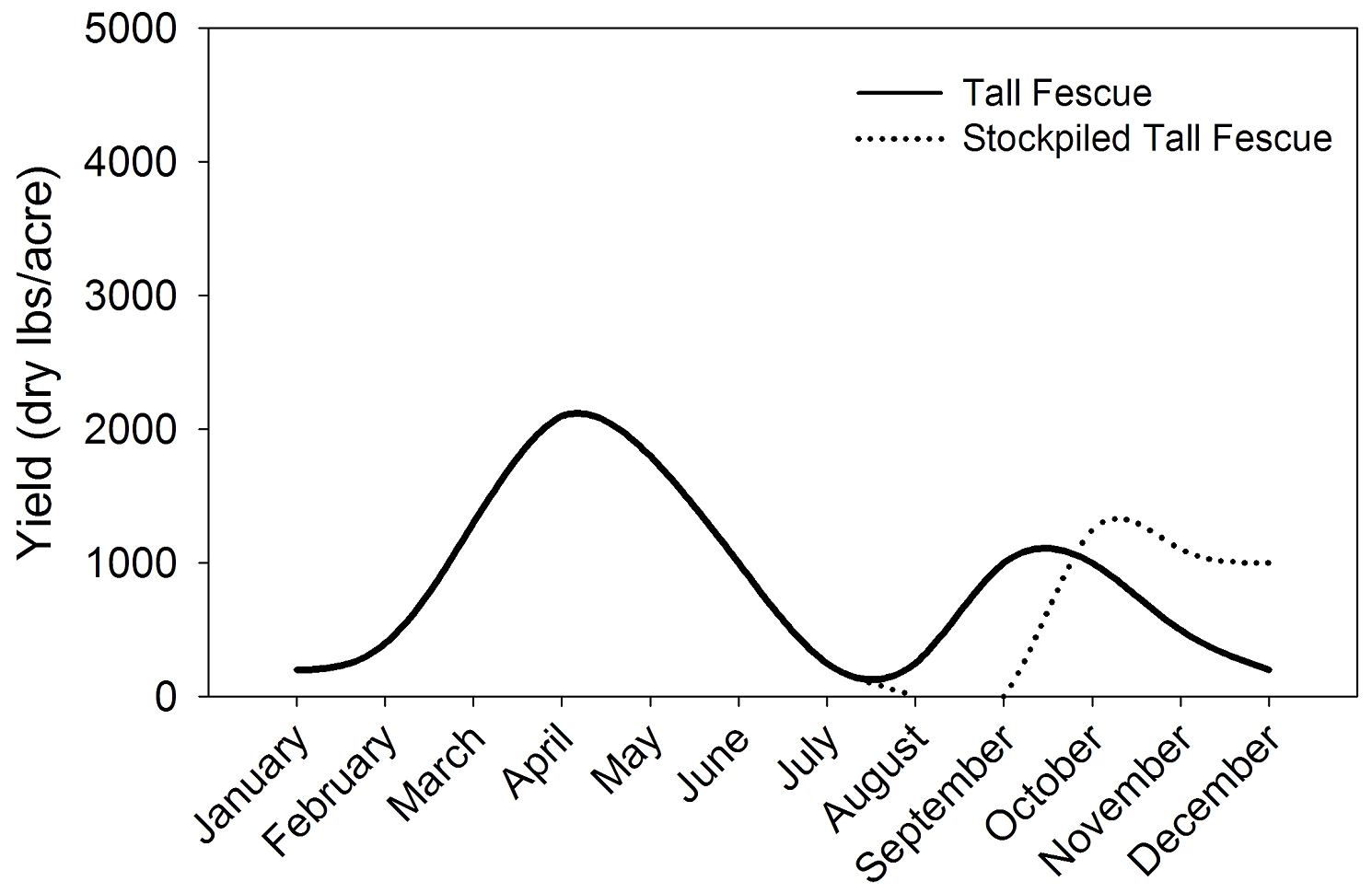

Fescue is a deep-rooted bunch grass that is productive during fall, late winter, and spring (Figure 2). More than half of the total yearly production occurs in spring. It does not grow well in mid-summer unless moisture conditions are favorable.

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Approximate distribution of available forage (dry lbs./acre) of tall fescue and tall fescue that has been stockpiled for deferred grazing.

A substantial flush of tall fescue growth will occur in the fall with sufficient moisture and an application of up to 60 lbs. of N per acre (Figure 2). This high quality forage can be stockpiled (allowed to accumulate) in pastures and hay fields from August through October and then grazed later in the fall and early winter. This deferred grazing (grazing after forage has been allowed to accumulate) of stockpiled forage can be an effective method for reducing winter feed costs.

Fescue produces its highest yields along creek bottoms in north Georgia. Production declines on hillsides and ridges as moisture becomes limited. Tall fescue does not persist well in the Coastal Plain region under normal growing conditions.

Tall Fescue ( Lolium arundinaceum)

Tall Fescue ( Lolium arundinaceum)

Use tall fescue for grazing and hay production. Forage quality and feed distribution are improved when an adapted legume (such as white clover or red clover) is grown in association with fescue. Close grazing (three to six inches) keeps forage quality high and helps keep clover in the stand. Unlike bermudagrass, fescue does not respond to exceptionally high N rates. Tall fescue pastures that are on productive sites can benefit from up to 100 lbs. of N per acre and support a high stocking rate. However, most fescue pastures in north Georgia are moderately stocked and are on marginal sites that will receive no benefit from N applications in excess of 50 lbs. of N per acre. If clover comprises less than 15 percent of the stand, treat it as a grass stand. Reduce N rates to 20 to 30 lbs. per acre if the stand contains 15 to 35 percent legumes. If the stand contains more than 35 percent legumes, no supplemental N is needed.

Tall Fescue Toxicosis:

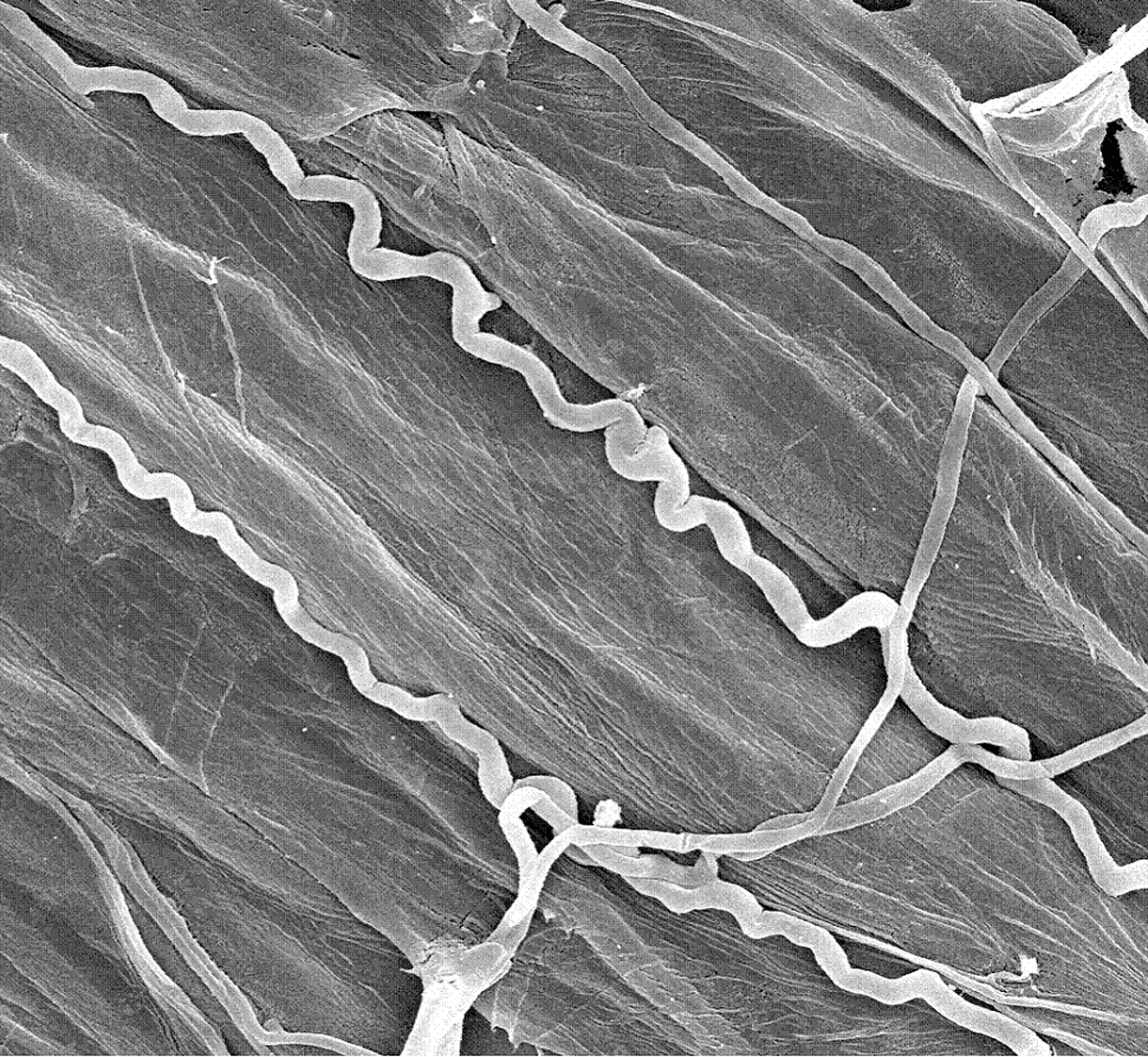

The vast majority of tall fescue that survives in pastures in Georgia is infected with a fungus that grows inside the plant and is transmitted in the seed. This fungus (Neotyphodium coenophialum) is called an endophyte. "Endo" (within) and "phyte" (plant) together mean an organism that lives within a plant (Figure 3). The terms “fescue fungus,” “fungal endophyte,” and “fescue endophyte” are common terms used to describe this same fungal organism that grows within endophyte-infected tall fescue.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. The slender tubes of the endophytic fungus

(Neotyphodium coendophialum) in the inter-cellular spaces of tall fescue.

Photo Credit: Dr. Nick Hill, ½ûÂþÌìÌÃ.

The wild- or native-type endophyte (E+) produces toxins called ergot-alkaloids. Highest concentrations of the toxins occur in the stems, leaf sheaths, and seeds. These alkaloids adversely affect livestock that graze infected pastures or consume hay cut from infected stands.

Livestock that consume E+ tall fescue may suffer reduced conception rates, decreased weight gain, decreased milk production, constricted blood flow (especially to extremities), slightly elevated body temperature, heat intolerance (animals stand in the shade more than normal), excessive nervousness, and failure to shed winter hair coats in the spring. These problems are collectively referred to as “fescue toxicosis.” (See for more on fescue toxicosis.)

The E+ infection level within a fescue pasture can range from low to very high. Research at the USDA-ARS Research Station at Watkinsville has shown a direct negative correlation between E+ infection level and animal gains. A 10 percent increase in E+ infection level reduces animal gains by about 0.1 lbs. per day.

The first step in developing a strategy to deal with fescue toxicosis is to determine the severity of the problem in your operation. Animal performance is the best indicator. Problems are minimal in operations where the calving percentage is more than 90 percent and calf weaning weights exceed 500 lbs. On the other hand, lower calving percentages and low weaning weights indicate a significant problem with either the fescue or the cow management program.

In pastures that have low levels of E+ tall fescue (less than 30 percent), the toxins can by diluted by interseeding legumes (usually white clover or red clover) or planting other grasses (e.g., bermudagrass, orchardgrass, etc.). These practices will be less effective when E+ tall fescue occupies more than 30 percent of the pasture. Renovation is the best option for pastures that are predominantly E+ tall fescue (60 percent or greater).

It was found that the endophyte imparts some very positive characteristics in the tall fescue plant that it infects (pest resistance, drought tolerance, persistence under grazing, etc.). Endophyte-free (E-) varieties are sold and have been used in Georgia since the 1990s. Unfortunately, research has shown that E- varieties fail to persist well under less-than-ideal growing conditions. As a result, E- tall fescue varieties are not recommended in Georgia.

Figure 4.

Figure 4. Cattle on E+ tall fescue pastures (foreground) spend less time grazing, while cattle continue to graze NE tall fescue (in back ground).

Photo Credit: Dr. Jane Parish.

More recently, tall fescue varieties have become available that are infected with a “novel” or “friendly” endophyte (NE). This novel-endophyte imparts essentially all the positive agronomic characteristics of a wild-type endophyte, but without producing any of the ergot alkaloid toxins (Figure 4). Although the cost per lb. of NE tall fescue is substantially greater than other tall fescue types, the investment is well worth it. Economists from ½ûÂþÌìÌà have closely examined this practice and have found that replacing E+ tall fescue with NE tall fescue is a cost-effective strategy for nearly all forage-based livestock systems in Georgia. As a result, NE tall fescue is recommended for all new plantings of tall fescue pasture or hay.

When purchasing NE tall fescue seed, care should be taken to ensure that the product is fresh (less than one year old) and has been stored in a cool, dry place. Seed that is old or has been stored in hot, humid conditions will cause some or all of the endophyte to die.

Information about recommended tall fescue varieties may be found on the “” webpage.

Renovating Infected Fescue Pastures:

Completely renovating an E+ tall fescue pasture to establish an NE tall fescue variety is a major operation. The renovated pasture will be out of production for eight to nine months. Make plans to supply extra feed or reduce cattle numbers during this period. There are four steps in this renovation program: preventing seedhead production in the existing E+ infected stand, destroying the existing stand, seeding the new variety, and managing the new planting.

Step 1: Preventing Seedhead Production.

The endophyte in tall fescue is spread via seed. If seed is produced by the existing stand of E+ tall fescue, then the chances are high that E+ plants will regenerate in the new stand. Therefore, it is critical to prevent the existing stand of tall fescue from producing a seedhead. Stands should be mowed when seedheads begin to develop but before they fully emerge. Two such mowings prior to viable seed production are normally required to prevent seed formation. Heavy grazing may prevent some seedhead production, but it may merely delay seedhead emergence. Therefore, it is likely that mowing will be required.

Step 2: Destroying Old Stands.

There are two methods for destroying an existing stand of E+ tall fescue. The first method is generally referred to as the “spray-smother-spray” method. This involves preventing seedhead formation as described above, spraying the existing stand with a moderate to heavy rate of glyphosate (commonly known by the trade name Roundup), growing a smother crop (usually a warm season annual grass, such as pearl millet) during the summer, and then spraying surviving tall fescue plants and weeds again in the fall with a moderate to heavy rate of glyphosate before planting the new stand. Unfortunately, this method is very expensive and more problematic for most small producers than the “spray-spray-plant” method.

The “spray-spray-plant” method was developed by researchers at ½ûÂþÌìÌà who showed that spring seedhead suppression and an application of glyphosate (Roundup) in late summer and a second application made four to six weeks later (followed by planting within one day of the second application) will successfully kill the existing fescue. The timing of this application protocol is critical, as sufficient regrowth by the survivors of the first application is needed to get a complete kill.

Destroying the stand with an herbicide in either of these two methods will be faster, cheaper, and much more effective than multiple tillage operations. Plowing alone will not provide sufficient kill of the existing stand and is not recommended. However, there may be some cases where the preparation of a tilled seedbed is desirable. In this case, the same protocol of two herbicide applications (regardless of method) is recommended prior to seedbed preparation.

Step 3: Seeding the New Variety.

Figure 5.

Figure 5. Planting a NE tall fescue into a suppressed sod with a no-till drill.

Photo Credit: Di Hodges.

Planting with a no-till drill should follow immediately (within one day) after the second application of glyphosate has been made (Figure 5). Killing fescue pastures with an herbicide and sod-seeding into the killed sod is advantageous for pastures with severe slopes. Plantings can also be made into a firm, prepared seedbed. In the Piedmont region, successful plantings can be made between mid-September and late October. Plantings in the Limestone Valley/Mountains region should occur between early September and early October. Spring seedings are generally not successful and are not recommended. Regardless of region, a planting rate of 15 to 20 lbs. per acre is required for successful stand establishment.

Drought and insects frequently cause problems with fall seedings. Dry weather can reduce germination and delay seed emergence. Stands that are not well-established by December can winter-kill. Insects (grasshoppers and pygmy mole crickets) that inhabit the fescue sod can damage new seedlings. Planting fescue into a prepared seedbed is often more successful than sod-seeding with a no-till drill. Seedlings emerge faster from a prepared seedbed, are more mature by late fall, have more cold tolerance, and are resilient to insect damage.

Step 4: Managing NE Tall Fescue.

Like all tall fescue plantings, new plantings need special treatment. Do not cut or graze new plantings until they have grown at least six inches. Even then, only a light grazing is recommended to avoid stand damage. A light mowing can help control weeds and encourage the tall fescue to grow and thicken-in (i.e., tiller); however, care should be taken not to cut tall fescue below a height of six inches in the spring following establishment. An early cutting of hay (prior to May) should not be taken from new seedings of tall fescue. If the NE tall fescue has been clipped to control weeds in early spring, a late cutting of hay (after mid-May) can be successfully made if the planting resulted in an acceptable stand.

Soon after the stand has been established (April or May following a fall seeding), NE tall fescue should be tested for the extent of novel endophyte infection. This will ensure that the NE is present in the tall fescue, that at least 80 percent of the tall fescue contains the NE, and that little or no E+ tall fescue is present. More information on testing the endophyte status of tall fescue stands can be found on the .

Although NE tall fescue generally is as persistent

Status and Revision History

Published on Jan 20, 2009

Published with Full Review on Jan 24, 2012

Published with Full Review on Jan 23, 2015

Published with Minor Revisions on Dec 13, 2018